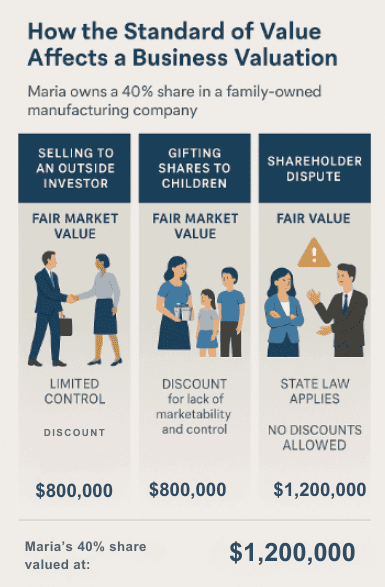

When it comes to valuing a business, the numbers tell a story, but how that story is interpreted depends on the standard of value used. Whether you’re gifting shares, going through a divorce, preparing for a sale, or navigating a shareholder dispute, understanding the three, most-common standards of value are important.

At LGA, we often tell our clients: Choosing the wrong standards of value for your business valuation isn’t just a technical error — it can be a costly one too.

Three Standards of Value

1. Fair Market Value (FMV): This most commonly used value is for estate and gift valuations. FMV is the price a business would sell for between a willing buyer and a willing seller, both having reasonable knowledge of the facts, and neither being under any compulsion to buy or sell. Think of FMV like the appraised value of a home; it reflects what the market would reasonably bear, not what the owner hopes to get or what a buyer wants to pay.

Key Features:

– Assumes hypothetical buyers and sellers, and may include discounts for:

– Lack of control (minority owners have less decision-making power), or

– Lack of marketability (closely held shares are harder to sell).

Widely used in:

– Estate and gift tax reporting (per Revenue Ruling 59-60)

– Gifting of ownership interests, or

– Sales to unrelated third parties (though discounts are seldom applied in actual negotiated transactions).

2. Fair Value (FV): This value is used in shareholder disputes, divorce cases, and financial reporting. It is a legal or accounting concept of value, typically defined by statute or professional standards, and often excludes marketability or control discounts. For example, in Massachusetts and several other states, such discounts are generally not applied in divorce proceedings or shareholder disputes. Misapplying fair market value in a fair value context can lead to incorrect valuations and costly legal backtracking, particularly when litigation is involved.

Key Features:

– Most often used in litigation settings, including:

– Shareholder or partner disputes,

– Divorce proceedings, or

– Financial reporting under GAAP/IFRS.

– Varies state-by-state.

When to Use FV:

– In shareholder disputes, particularly for buyouts involving closely held companies,

– In equitable distributions (such as divorces or forced buyouts), or

– When GAAP compliance is required in reporting.

3. Investment Value (a.k.a. Strategic or Synergistic Value): The buyer’s-eye view, typically used in mergers and acquisitions, this value is for a specific buyer based on their unique circumstances, expectations, or synergies.

Key Features:

Often results in a higher value than Fair Market Value (FMV) because it includes benefits unique to a specific buyer:

– Cost savings (e.g., eliminating duplicate expenses post-merger),

– Revenue opportunities (e.g., cross-selling to a larger customer base), and

– Strategic alignment with the acquirer’s goals.

– Based on the perspective of a specific buyer, not a hypothetical market participant.

Used In:

– Mergers and acquisitions,

– Negotiated deals with strategic buyers,

– Internal transitions where the successor brings unique synergies or advantages.

How Discounts Change the Game

In FMV and some litigation scenarios, valuation discounts can dramatically reduce reported value. The two most commonly used discounts are:

- Lack of Marketability Discount (DLOM): Applied to reflect how hard it is to convert a closely held interest into cash.

- Lack of Control Discount (DLOC): Reflects the reduced value of a minority ownership interest due to limited or no ability to influence key decisions, such as declaring dividends, setting compensation, or initiating a sale of the business.

Combined, these discounts can reduce an ownership interest’s value by varying amounts, often by 30% to 40% or more, depending on the company and market conditions. However, in “Fair Value” states, like Massachusetts, these discounts are not applied in shareholder disputes or divorces—emphasizing the importance of understanding your jurisdiction.

Why Choosing the Right Standard of Value Matters

Whether you’re planning to sell, gift, or transfer ownership of a business, understanding the standard of value is more than a technical detail; it’s a strategic decision that directly impacts your financial, legal, and tax outcomes.

The purpose of the valuation dictates the appropriate standard. Get that part wrong, and the numbers that follow may be misleading, non-compliant, or misaligned with your goals. Purpose-Driven Standards include:

- Gifting shares to family members? You’ll need Fair Market Value (FMV), including discounts, to comply with IRS guidelines and maximize tax efficiency.

- Planning to sell to private equity? You’ll want to consider Investment Value, which accounts for forward-looking growth and buyer-specific synergies. This usually results in a higher valuation than FMV, which is valuable knowledge when negotiating a sale price.

- Facing a shareholder dispute in Massachusetts? You should use Fair Value, which excludes discounts. Applying FMV instead, which is a common mistake, can lead to legal challenges, unnecessary conflict, and costly litigation delays.

How the Standard of Value Shapes the Final Number

Choosing the right standard of value isn’t just an accounting technicality; it’s the starting line that sets the tone for every decision made during the valuation process.

Think of it like setting the ground rules before a game. Once the standard is defined, everything else (discounts, assumptions, adjustments) follows that framework.

What Happens When the Wrong Standard Is Applied?

One of the most frequent issues we encounter is the misuse of FMV in litigation settings, especially in states like Massachusetts, where the law requires Fair Value. Using the wrong standard can lead to:

- Valuation challenges

- Increased legal costs

- Delays in resolution

- Strained relationships between stakeholders

- Over or under-valuation of the business

- IRS penalties in estate or gift tax filings

- Inequitable outcomes in court

- M&A deals falling through due to inflated or deflated expectations

This isn’t just theory; it’s something we see regularly in real-world disputes. The wrong standard leads to the wrong result, and correcting that path can be both time-consuming and expensive

Start with the Purpose, Then Choose the Standard

Whether you’re preparing for estate planning, litigation, or a business sale, the first question should always be: “What’s the purpose of this valuation?” The answer then determines the standard and ultimately the outcome.

Remember, the standard of value is not just a line item; it’s the foundation for everything that follows. It can push your valuation up or down by 30–40% or more, depending on what it allows or excludes.

Need Help Selecting the Right Standard of Value?

If you’re preparing for a valuation, let’s discuss the standard that best aligns with your goals, whether that’s tax efficiency, legal clarity, or sale readiness.

LGA’s Business Valuation, Advisory, Tax & Forensic Accounting teams work closely with attorneys, business owners, and financial advisors to ensure the correct standard of value is applied every time. This ensures not only accuracy but also legal compliance and peace of mind.